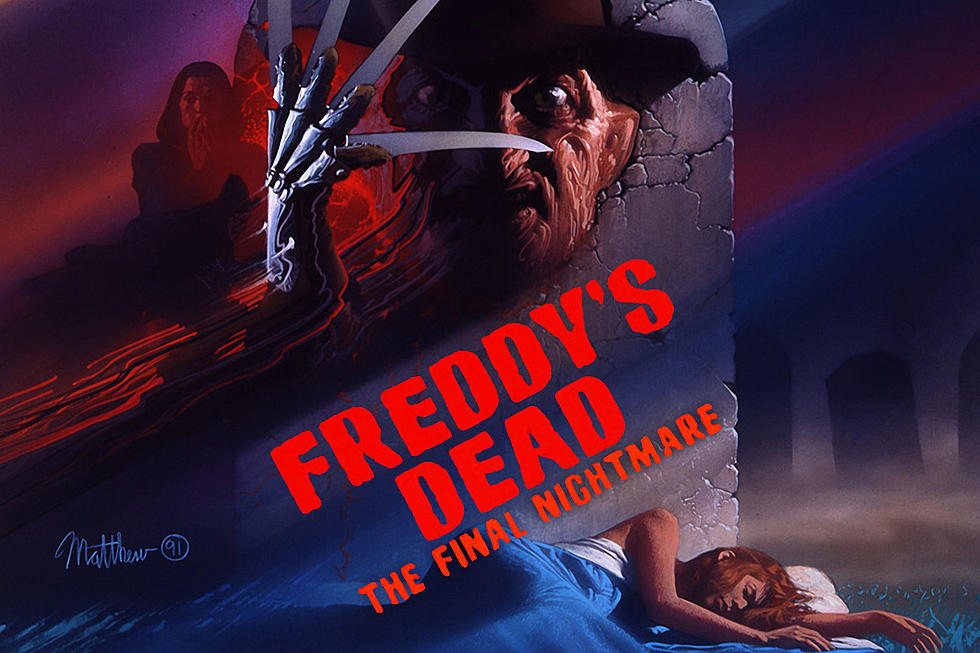

30 Years Ago: ‘Freddy’s Dead’ Swaps Terror for Trauma

Few horror sequels are as heavily maligned as Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare. Released on Sep. 13th, 1991, this sixth part of the A Nightmare on Elm Street saga has always been seen as a particularly egregious example of a once terrifying franchise becoming wholly ridiculous.

While that complaint remains somewhat valid, such criticisms undermine the richer thematic weight, crafty continuity and admirably innovative choices made by first-time director Rachel Talalay and screenwriter Michael De Luca.

Specifically, it’s a wildly imaginative love letter to its lineage whose fun sequences, compelling characters and intentional silliness often mask its downright troubling and profound commentary on the cycle of trauma. It may not be the best entry by traditional standards, but it is possibly the most audaciously distinctive and authentically disturbing.

Watch the Trailer for 'Freddy's Dead: The Final Nightmare'

Obviously, Freddy’s Dead didn’t really mark the end of the franchise. At the time, however, New Line Cinema very much intended it to be the last Nightmare. After all, 1989’s A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child earned less than half of its predecessor, and as producer Bob Shaye admitted in the Never Sleep Again documentary, the creative team was “truly running out of good ideas,” so it was “time to move on” and focus on other projects.

Having been involved with several previous Nightmare films (to varying degrees), Talalay urged Shaye to let her make her directorial debut. She even drafted a plot outline to prove that she had the correct vision. “We would kill off Freddy . . . [and] create more story than had been there for Nightmare 4 and 5,” she explained in an interview for the Nightmare Series Encyclopedia documentary. Naturally, Talalay got the job – making Freddy’s Dead the only Nightmare movie directed by a woman, and the only one in which no main female characters die – but as usual, the script went through several changes before shooting began.

Fascinatingly, both Michael Almereyda and Peter Jackson came up with intriguing ideas (involving returning figures from the past three chapters, as well as a severely emasculated Freddy) that Talalay ultimately rejected in favor of the route she and De Luca desired to take. “I was conscious of wanting to make a slightly more fun piece,” she remarked in the Nightmare Series Encyclopedia chat, noting that her earlier work on John Waters’ projects like Cry-Baby – alongside her recent viewings of 1962’s Carnival of Souls and an influential new TV show called Twin Peaks – led to “a lot of the weirder ideas” and numerous cameos in Freddy’s Dead.

Watch the Opening Scene From 'Freddy's Dead: The Final Nightmare'

Unfortunately – and despite its forward-thinking approach, novel promotional tactics, and considerable profitability – the film still bombed with critics (due mostly to its persistently sophomoric slapstick). Thirty years later, however, Freddy’s Dead deserves closer examination.

Every prior Nightmare entry is alluded to in the film. For example, Maggie returns home to confront her mother about the past, just like Nancy did in the original; Freddy uses John Doe to keep his legend alive, as he did with Jesse in Freddy’s Revenge; Maggie’s role as a surrogate leader to a group of troubled teens evokes Nancy’s position in The Dream Warriors; Tracy’s interest in marital arts mirrors Rick’s kung fu fascination in The Dream Master; and Spencer’s video game death recalls Marks’ comic book demise in The Dream Child. As much as it may seem like Freddy's Dead bastardizes its legacy, it actually builds upon it in many ingenious ways.

Watch the Video Game Death From'Freddy's Dead: The Final Nightmare'

The film encompasses some of the most creative and aspiring nightmares in the franchise, too. From John’s complex opening turmoil and Spencer’s aforementioned psychedelic peril, to Carlos’ derelict torment and Tracy’s homegrown cruelty, Freddy’s Dead doesn’t skimp on elaborate and disconcerting ventures into the subconscious. Add to that some truly effective uses of shaky cam and sound design (especially during Carlos’ fantasy) and you have an experience that’s equally fun and frightening.

Easily the greatest attribute of Freddy’s Dead, though, is its exploration of physical and psychological trauma. Nearly every main character – including Freddy – is given a backstory involving some kind of childhood anguish that’s impacted who they’ve become. Specifically, Carlos’ mother disciplined him so severely that he became deaf; Spencer’s father demanded that he follow in his footsteps; Maggie witnessed her father kill her mother after she discovered that he was a child murder; and Freddy – in typical serial killer fashion – suffered so much abuse at home and at school that he became a sadistic killer.

Of course, you can’t discredit what’s arguably the most upsettingly universal representation of all: Tracy’s sexual abuse at the hands of her drunkard father. In Never Sleep Again, actress Lezlie Deane reveals that the role – and particularly, her nightmare sequence – “came really easy” to her because she “started getting flashes of being molested” in real life. “It pulled a scar back. That scene actually changed my life. It sent me on a journey . . . dealing with my own fears,” she expounded.

More than any other Nightmare offering, this one even examines how the death of dozens of Elm St. kids affected their parents and the Springwood community as a whole. Be it the almost apocalyptic carnival scene, the nonsensical ramblings of the elementary school history teacher, or the imaginary children spoken to by the woman at the adoption center, Freddy’s Dead sheds new light on the lingering aftermath of Krueger’s carnage.

Freddy’s Dead has many weaknesses, but it also has many strengths that make it far more praiseworthy than most viewers think. Beneath its persistent goofiness – which is still enjoyable – lies a deceptively deep and resonant assessment of trauma in all of its multigenerational and multifaceted forms. Coupled with some sly satire, self-referential gems, solid acting, and inspired situations, that focus allows Freddy’s Dead to endure not only as the funniest entry in the series, but also as perhaps the most nuanced, ambitious, contemplative and generally misjudged one.

The Best Horror Movie From Every Year

More From Sasquatch 92.1 FM