Edgar Winter, ‘Brother Johnny': Album Review

Large-cast all-star tribute albums are usually a buyer-beware proposition. Too often they're slapdash and unfocused, a concept put together in somebody's office that looks good, or at least potentially good, on paper but doesn't quite gel in the studio. Brother Johnny, fortunately, is a rare exception. Eight years in the making, it's a musical love letter from Edgar Winter to his older brother Johnny, the blues-rock great who died in 2014 at the age of 70.

It's big - 17 tracks, 76 minutes - and filled with A-list names, especially on the guitar front. But Brother Johnny is a true labor of love, and every second is filled with a genuine passion and regard for a guy who, despite no longer being still alive and well, left a great deal of excellent music that's still with us and gets its proper due on this tribute. More than 50 years on, some rock fans may not recall or may have never known about the impact Johnny Winter made when he emerged from Beaumont, Texas, getting a recording contract - reportedly for a record advance of $600,000 - after Mike Bloomfield invited him to jam with him and Al Kooper at the Fillmore East.

With his long blond hair and albino skin, Winter was a visual shock, while his electric blues was a shock to the system that immediately vaulted Winter into the upper echelon of guitar heroes. Edgar Winter was along for the ride on brother Johnny's first two albums and at Woodstock, and he famously brought him back from a substance-induced hiatus with a guest appearance on Roadwork, the 1972 live album by Edgar's band White Trash. The Winters worked together on and off throughout Johnny's life, making his brother the only one qualified to helm this kind of tribute. Brother Johnny manages to be a lot, but not too much of a good thing. It's driven by Edgar's vision but also the presence of a single drummer, Gregg Bissonette (save for Ringo Starr on "Stranger"), which gives the set a cohesive rhythmic personality that's subtle but certainly felt. There are only two bassists - Sean Hurley and Bob Glaub - as well, which means the foundation is strong for the assembled guests to shine in Winter's honor.

And that they do. Brother Johnny is the kind of affair where you can drop the needle just about anywhere and find something to be excited about. It starts at a high-speed shuffle, with Joe Bonamassa's slide stinging through "Mean Town Blues," while Kenny Wayne Shepherd and Bon Jovi's Phil X put crunch into "Still Alive and Well." Billy Gibbons and Derek Trucks duel their way through a lusty, meaty "I'm Yours and I'm Hers," and Joe Walsh provides the lead vocal on Chuck Berry's "Johnny B. Goode, with David Grissom performing the guitar heroics. Walsh then picks up his axe for an aching "Stranger," sung by Michael McDonald.

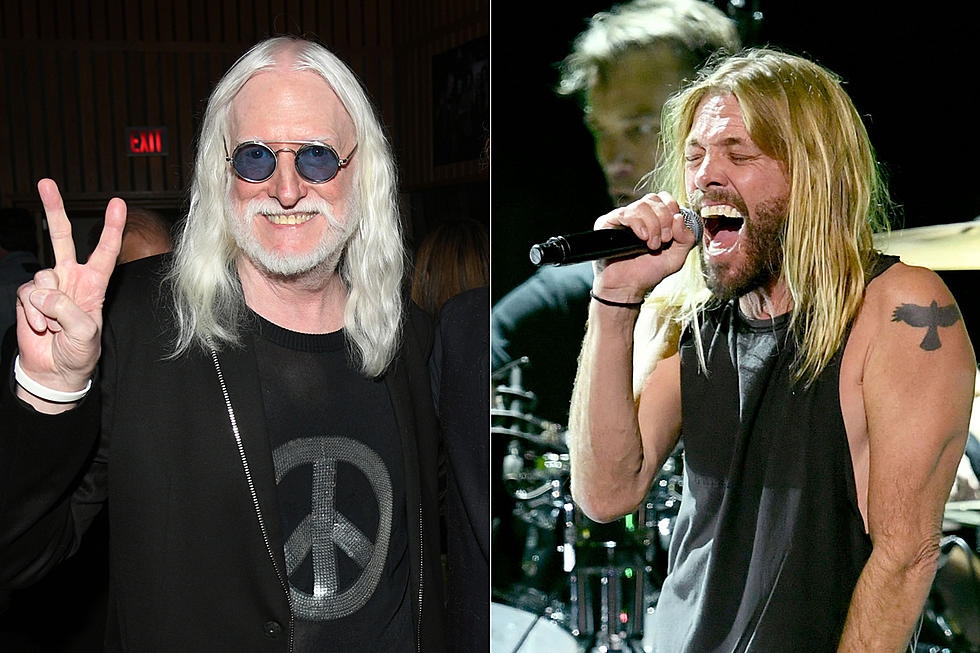

It goes like that throughout Brother Johnny. Shepherd and the Doobie Brothers' John McFee lock horns over Edgar's striding guitar line in Bob Dylan's "Highway 61 Revisited," and Edgar takes the lead vocal on "Rock 'n' Roll Hoochie Koo," with Steve Lukather soloing. Gov't Mule's Warren Haynes grinds out some gritty funk on "Memory Pain," and veteran bluesman Bobby Rush is an inspired choice, on vocals and harmonica, for "Got My Mojo Workin'." There are quiet moments, too - rustic, front-porch takes on "Lone Star Blues" with Keb' Mo' and "When You Got a Good Friend" with Doyle Bramhall II," while a horn section accompanies Edgar on a slow take of Ray Charles' "Drown in My Own Tears," while a string quartet-sweetened "End of the Line," which closes the festivities, draws a few tears of its own. And it's hard not to be moved by the presence of Foo Fighters' Taylor Hawkins, who died suddenly just three weeks before Brother Johnny's release, on a hard-hitting version of "Guess I'll Go Away." There was a sense that, even at 70, Johnny Winter was gone too soon, and his recent albums such as Roots and the posthumous, Grammy Award-winning Step Back certainly supported that notion. Brother Johnny celebrates the six-string stallion that he was, and hopefully, this salute can serve as a portal to send listeners back to explore the original works.